Prohibition’s historic calamity of the sinking Whisky Ship

Official story: It was carrying coal

Every piece that comes through Miller & Miller Auctions has a story, a history. Sometimes those stories are legendary and live on in perpetuity.

The tale of the booze-filled ‘Whisky Ship’ that sank off the shores of Port Rowan in the height of Prohibition is one of them.

At their Feb. 10, 2018 Canadiana & Decorative Arts sale, Miller & Miller brought the hammer down on a painted wooden sign, known as the name board, from the ill-fated Canadian Whisky Ship whose official name was The City of Dresden. When it hit the waters in November 1922, the historic alcohol ban in Canada, known as Prohibition, was in full swing.

The decrepit wooden steamer, launched in the Detroit River, sank in a violent Lake Erie storm that November while carrying 1,000 cases and 500 kegs of Corby’s Old Crow whisky worth $50,000. The official story was it was carrying coal.

The 28-metre long, propeller-driven steamer was torn apart by 15-meter (50-foot) waves in the raging storm and sank just west of Port Rowan, Ontario near Long Point, clearly in view of the shoreline in just nine meters (30 feet) of water.

The event has been called a tragic comedy, an historic calamity due to the antics than ensued on shore.

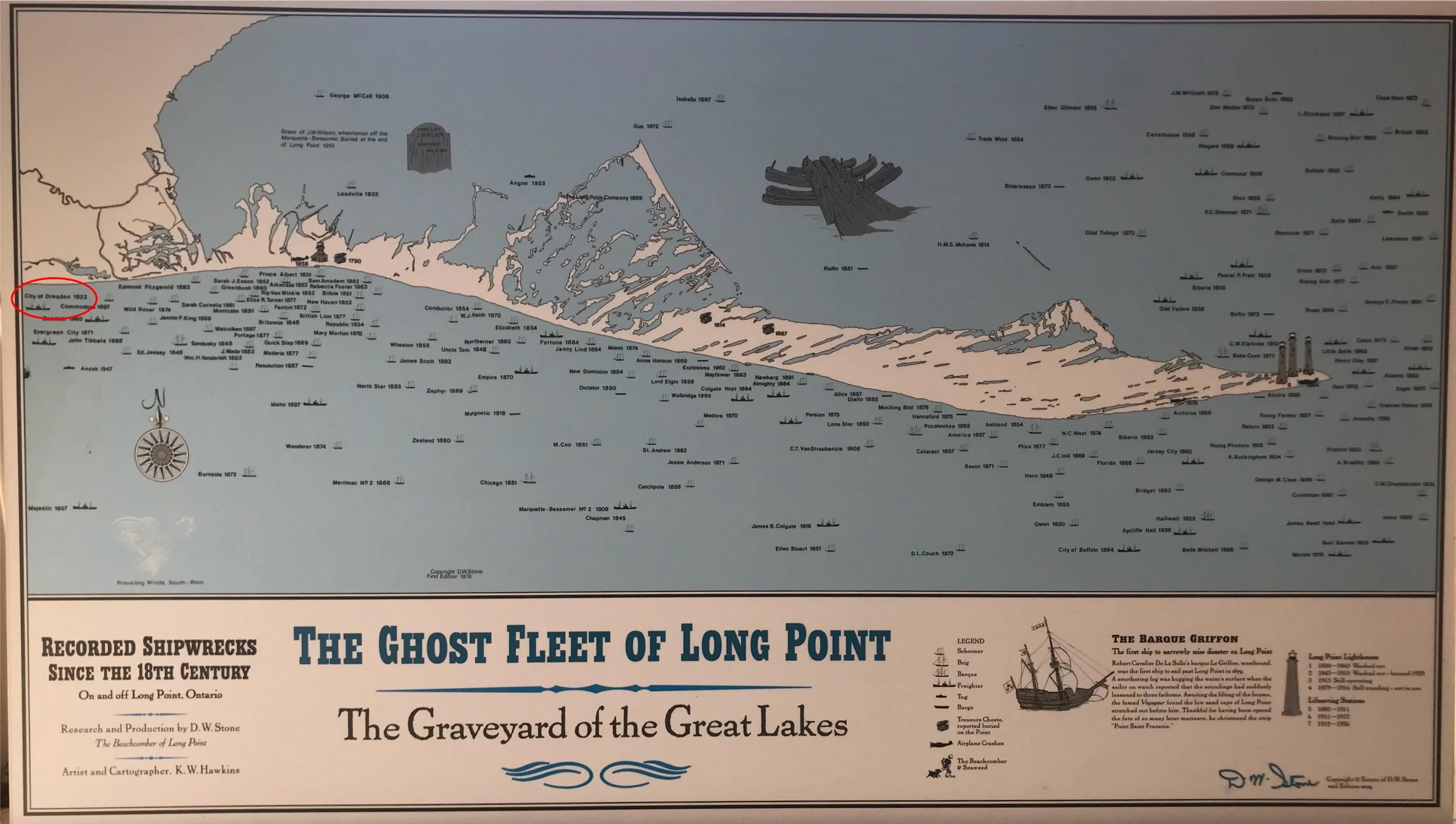

The Long Point area has earned the notorious nickname “The Graveyard of the Great Lakes” due to the astounding number of shipwrecks off the coastline. The wreck-site of the City of Dresden is circled in red at the far left of the image. Source.

Sadly, the captain’s 21-year-old son drowned in the storm while trying to save another crew member who did survive. Meanwhile, the ship’s cargo was strewn about and began to land ashore bottle by bottle, cask by cask. Word spread as nearby residents scurried to become the beneficiaries of the ship’s catastrophic fate.

A lone patrolman from the lifesaving station was among the first to discover the bounty. Well aware of the laws against liquor, he is said to have buried over 40 kegs and cases of the whisky, using telephone poles as markers.

The Dresden’s loud distress call also summoned other residents who began gathering on shore, some to help land the crew’s lifeboat, others to ‘rescue’ the cargo. There are various stories about who saved the men on board.

“Whoever did it, the crew was saved and hustled into warm houses. Then the fun began in earnest for the people of the Long Point area,” writes Gordon Lawrence using information from Harry B. Barrett’s 1979 book, Lore & Legend of Long Point. “As the ship tore apart, cases, kegs and bottles were scattered along the beach. News of the wreck and its cargo spread like wildfire throughout the district. People of every walk of life, in every imaginable form of conveyance soon converged on the beach west of Port Rowan. Whisky was trucked, teamed or carried off in bags all night long and well into the following day. Some people buried a great deal in the sand or in the swamps nearby. Others noting their neighbours’ catches, returned when it was quiet to dig them up.”

Undoubtedly, there were many who disliked adhering to the ‘dry’ life and welcomed the opportunity to scoop up The Dresden’s spoils.

“Prohibition was then in full force in both the U.S. and Ontario, ironically with alcohol production still being allowed in the province for either export or for pharmacies that filled doctors’ prescriptions for medicinal purposes,” wrote maritime historian and author Cris Kohl in a January 2023 Windsor Star column. “Local residents near Long Point saw to it their ‘medicinal needs’ would be satisfied for a long time to come. Nearly every bottle of Canadian alcohol on board the City of Dresden found a good home or was secreted in barns or cached in the surrounding marshlands for future retrieval.”

Workers pour liquor down a sewer following a raid during the height of prohibition in the U.S. The American black market was often supplied by Canadian firms still permitted to produce booze for medicinal use and export. (Library of Congress/Reuters) Source.

One elderly man was reportedly discovered drunk, straddling a full keg of whisky with an open bottle in each hand, shouting “this keg is mine, all mine and there ain’t nobody going to get her away from me”.

As James M. Clemens writes in his book Thirst! A Story of Prohibition In Ontario, “Prohibition was the law of the land in both Ontario and the United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Yet because of the one key difference between Ontario’s Temperance Act and America’s Eighteenth Amendment, smugglers could make small fortunes transporting Ontario booze through the Great Lakes to harbours in America.”

Attempts by Canadian police and Temperance authorities to track down the Dresden’s cargo and the offending absconders were largely unsuccessful.

The name board from the Whisky Ship that sold at Miller & Miller’s 2018 auction was autographed by those involved in the historic incident, including by R. ‘Dickie’ Edmonds, the Government Liquor Inspector at the time. Estimated to bring CA$3,000 to $3,500, the sign sold for $5,900, giving the successful bidder a piece of legendary maritime history well worth raising a toast to!

Government Liquor Inspector R. ‘Dickie’ Edmonds’ signature on the name board.