Traders Bank failed to ‘account for’ human nature

An original Traders Bank Architectural Savings Bank comes to auction

Offered as lot 234 in Miller & Miller’s January 21st sale is an original Traders Bank Architectural Savings Bank.

As the world gradually reclaims normalcy following the peak of the pandemic, Canada is faced with its next opponent: a tumultuous economic climate. As inflation and interest rates soar, stocks plummet, and the labour market reels from the Great Resignation, one fact prevails: Canadians have returned to spending money, and they’re spending more of it than ever before.

Despite its prosperous reputation, Canada actually has one of the lowest household savings rates in the world. This is a fact attributed to our high costs of living, goods, and services, in addition to our recreational - or “nonessential” - spending habits. To be fair, humans are consumeristic creatures by nature. In fact, a recent study suggests that consumption is a much stronger predictor of life satisfaction than income. Whether our purchases are experiential (i.e. booking a vacation), or materialistic (the art of collecting, perhaps), we often feel a sense of gratification when completing the transaction. There’s an old saying that many collectors will identify with: “if you’re not buying, you’re dying”. This truth, in combination with our ever-increasing cost of living, leaves many Canadians with little ‘extra’ for saving.

History suggests that fuelling a savings account may have also been a challenging concept for Canadians of generations past. Case in point: the failure of the late 19th century Traders Bank of Canada Savings Program.

The Traders Bank of Canada was established in the 1880s and operated until its acquisition by the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) in 1912. It was one of 39 independent chartered banks in operation before the revision of the Bank Act in 1890, a restructuring which paved the way for our “Big Five” banks of today. Prior to the revision of the act, chartered banks such as Traders issued their own local bank notes as currency. After a number of bank failures in the 1850s and 60s, confidence in these banknotes diminished and the government decided a more formal, regulated banking system was required.

A five-dollar bank note from The Bank of Hamilton, 1892. Source.

A four-dollar bank note from The Colonial Bank of Canada, 1859. Source.

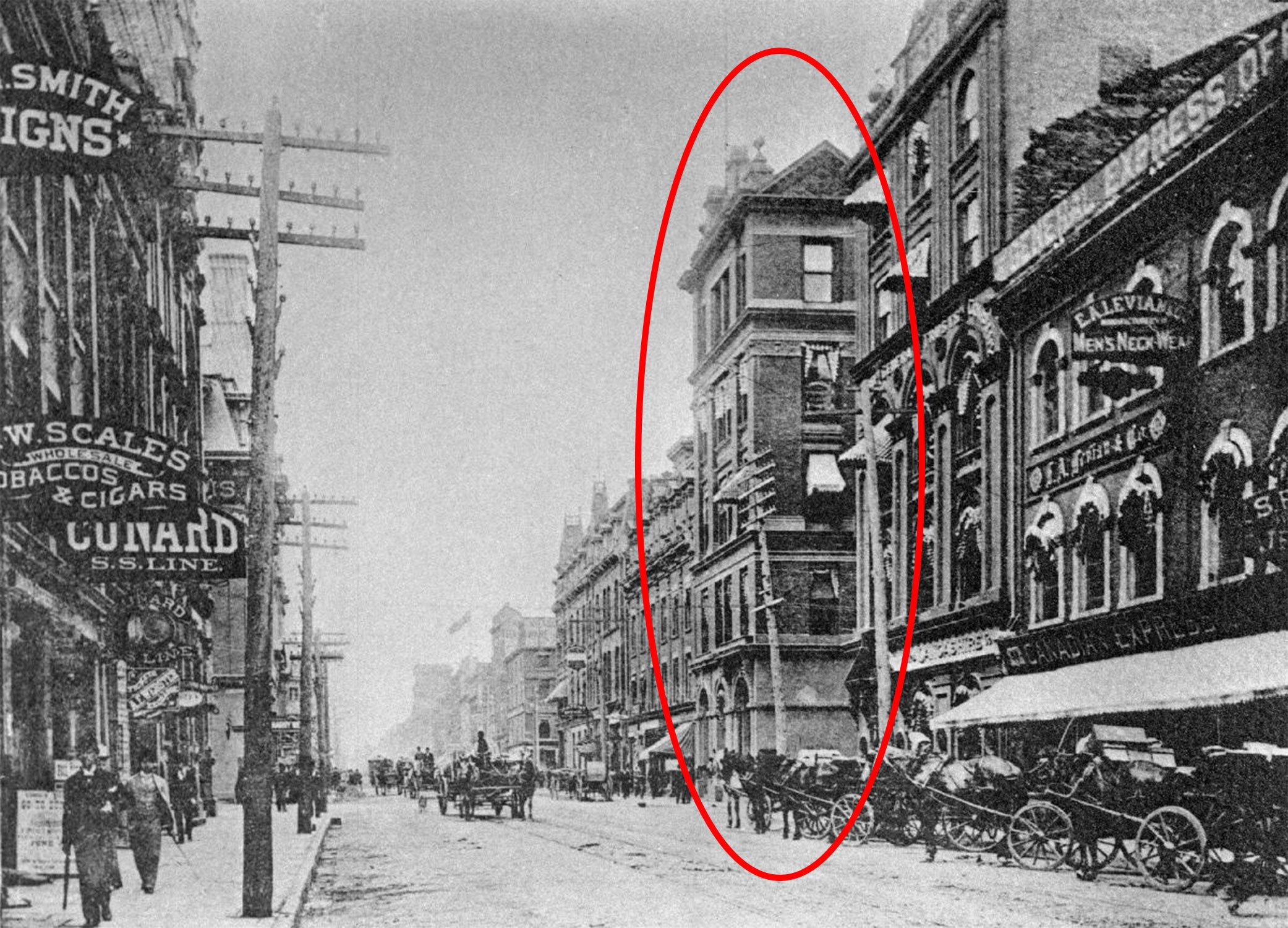

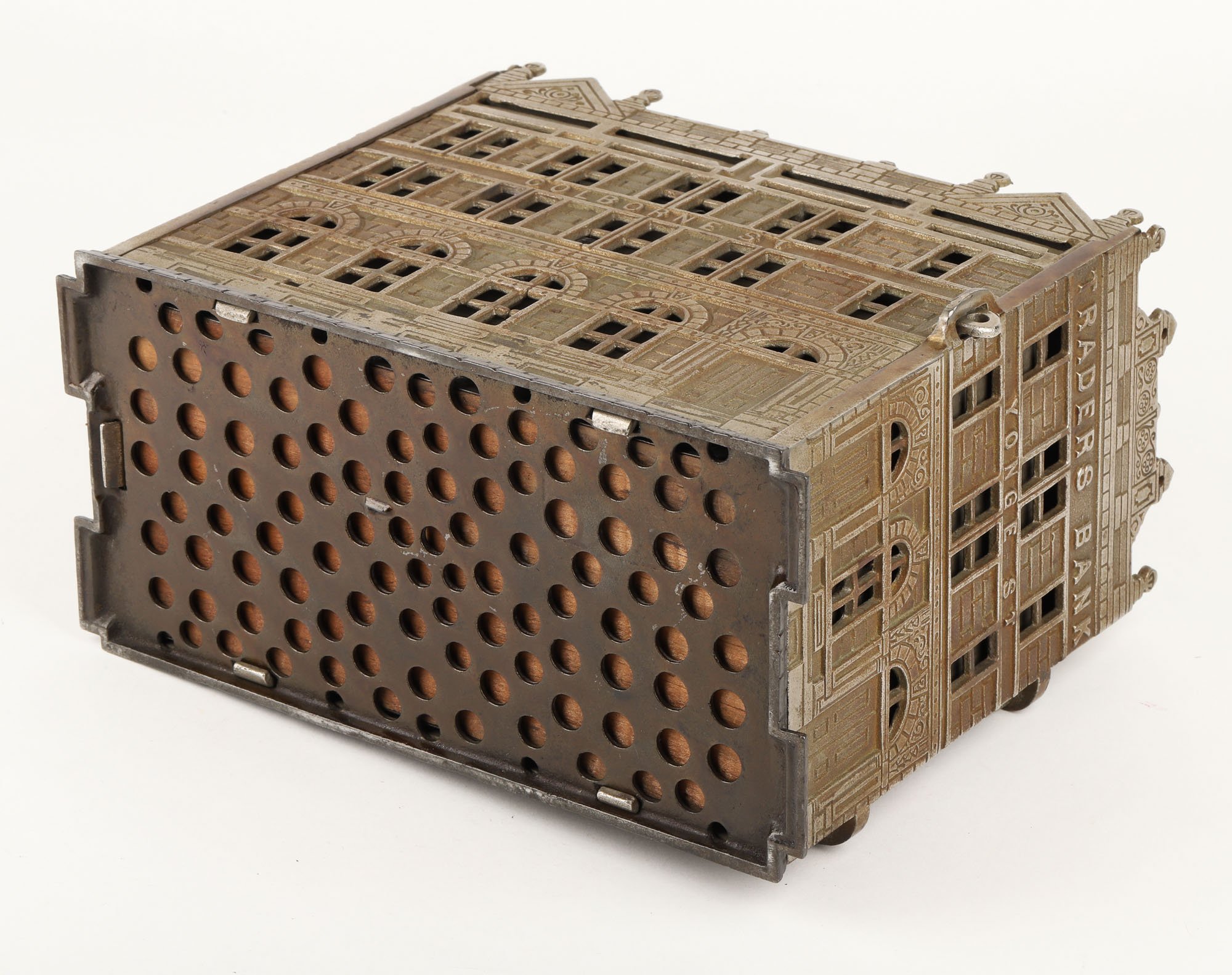

Due to the high number of direct competitors, early chartered banks were forced to get creative with customer incentives and loyalty programs. In 1891, Traders Bank developed a unique savings program which involved issuing customers a physical cast-iron bank to take home and deposit coins into. Each savings bank had a lock and only issuing authorities from Traders Bank could unlock it to deposit money at the institution. The banks were developed by the bank’s inspector, Aemilius Jarvis, who modeled them after the bank’s head office building in Toronto. Located at the intersection of Yonge and Colborne streets, the original building in which the bank is modeled after was torn down in 1905 and replaced by the still-standing ‘Traders Bank Building’. As photos of the original building are scarce, the replica banks are the best depiction of the previous structure.

A rare photograph of the original Traders Bank Building, taken from Yonge Street, just south of Colborne.

From the Graham J.F. Jones Collection and featured in his book Canadian Penny Banks (p.27-8), Miller & Miller Auctions is pleased to offer an exceptional cast iron Traders Bank in the January 21st sale of Advertising & Historic Objects. The bank is debossed on top, "Property of Traders Bank of Canada Registered by AE Jarvis 1891 The Traders Bank Sole Licensee". One side is embossed, "The Traders Bank of Canada", while the other side is embossed, "Colborne St". Both ends are embossed, "Traders Bank, Yonge Street”. The bank is accompanied by an original Traders Bank banknote and two branded pens, also featured in Jones’ book.

While some American banks had already implemented this type of saving system, Jarvis’ unique design of the bank itself is considered exclusively Canadian. It included four outer coin slots along the roofline, each placed directly above one of four separate compartments inside. Each compartment was stamped with a unique bank account number: one for each member of the family. Customers were encouraged to bring the bank into a branch once per week to deposit the contents. If customers were located outside of Toronto, travelling bank officials would make home visits once per month to retrieve the savings.

If you haven’t guessed already, the program was a total failure. The logistics, the labour, the travel time and the paperwork required resulted in an operation that was neither sustainable nor profitable. The program was abandoned not long after it began. It’s seems the art of saving has never been our strong suit in Canada. If anything, we should give credit to generations past for saving us from adopting the (ludicrous) task of lugging a cast iron bank around town, clattering with loonies and toonies. We’ll stick with our online banking applications, for now.

As for the cast iron banks? Nearly 1500 banks are said to have been either scrapped or sold off for a dollar per piece after the program ended. There were sightings of hundreds of the banks piled high into a warehouse, no doubt causing excessive damage (see Jones, p.28). Remarkably, unlike the ill-fated Traders Bank savings program, the example offered at Miller & Miller remains a true survivor.

Story by Tess Malloy

Tess is a freelance writer and history enthusiast who enjoys unearthing interesting stories about remarkable people and objects. Tess has written for The Miller Times for five years.

AUCTION DETAILS:

Advertising & Historic Objects

January 21, 2023. 9am EST.

Did you enjoy this story? Feel free to share it using the links below: