Missing arms, moving parts & gambling for cigars

Graham Jones reminisces about his bank and clock collecting

Many years ago, when Graham Jones was doing an antique show a fellow approached him saying he had an old bank shaped like “an ugly little man” that he wanted to sell. Jones said sure, he’d be interested to see it.

“It was a very rare American piece, but as far as he was concerned it was just a broken old bank with a missing arm.” Jones happened to know a guy in the States who sold original parts so he took a chance and bought it. As luck would have it, the American had the very arm he needed – “and so it became the perfect example.”

Jones bought the broken bank for $150, paid $50 for the replacement arm, then sold the bank for $10,000. No wonder it’s his favourite story.

“Most people are afraid to take things apart, but not me. I enjoy it.”

That’s because Jones, now 84, is a retired mechanical engineer who spent much of his career in research and development with the Ontario Ministry of Transportation. Understanding moving parts is his thing. So is taking them apart and fixing them, especially antique clocks and banks.

Jones’ personal collection is now being sold by Miller & Miller Auctions at their January 21, 2023 sale, Advertising & Historic Objects.

The engineer’s interest in antiques began in 1980, initially focused on clocks. He even enrolled in a three-year program at George Brown College in Toronto to learn how to repair them. “It just went from there,” he says. “After a while I met people who were interested in banks and I soon took them up too. But my main interest has been in everything Canadian.”

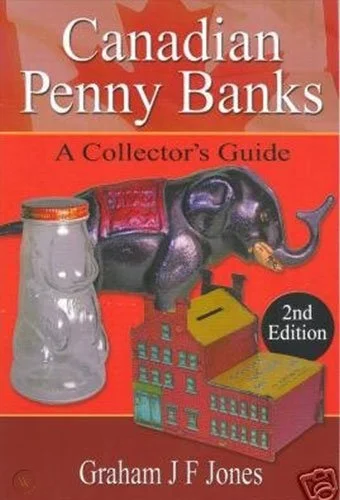

After retiring in 1997 he opened and ran an antique store in Oakville, Ontario for three years. He also turned his attention to research and writing – three books in all: His 2006 compilation on clocks is in Unitt’s Canadian Identification & Price Guide to Antique Clocks, Barometers & Sundials. And he self-published Canadian Penny Banks – A Collector’s Guide, a first edition in 2002 and a second, expanded edition in 2006. Until his books, very little was known about Canadian banks.

Jones’ compilation on clocks is included in Unitt's Canadian Identification and Price Guide to Antique Clocks, Barometers and Sundials

Jones self-published Canadian Penny Banks – A Collector’s Guide, a first edition in 2002 and a second, expanded edition (pictured) in 2006.

The reason there are so many more American cast iron banks than Canadian, he explains, is because after the 1860s American Civil War there was a glut of manufacturers experienced in working with cast iron looking for new business. That, and the fact that by 1880-1890 America was already a 100-year-old industrial nation while Canada was barely a country.

Later, manufacturers of Canadian banks copied American banks and when they used them as moulds, the Canadian version would be slightly smaller due to shrinkage during the casting process. Jones says almost all Canadian still banks were made by the Beaverton Toy Company in Beaverton, Ontario.

He adds that cast iron banks have been reproduced over the years by makers in the Far East, but suggests they’re quite easy to spot by the condition of the paint, the quality of the casting and the fit of the joints.

Some highlights in the upcoming auction include a very rare, circa 1900 ‘Old Quebec’ cast iron bank loosely based on a house in Quebec City known as Jaquet House (Lot 235). Jones travelled to Quebec to research it because he felt it was so important. There’s also a Trader’s bank (Lot 234) that replicates the majestic Trader’s Bank building in downtown Toronto, demolished in 1905. It was a Trader’s promotion that also encouraged saving. It had four chambers inside where family members could each deposit coins in their own slot as a way of saving. Only a Trader’s bank representative could unlock the bank to collect the coins for deposit to the respective accounts. But Jones says the program was a failure. Emptying the banks and doing the bookwork for such small deposits proved too time-consuming. After a few years, Trader’s retrieved the banks and tossed them in the bank’s basement, which is why the fragile finials on those that survived are often damaged.

This Old Quebec Architectural Bank is offered as lot 235 in the sale.

This Traders Bank Architectural Bank is offered as lot 234 in the sale.

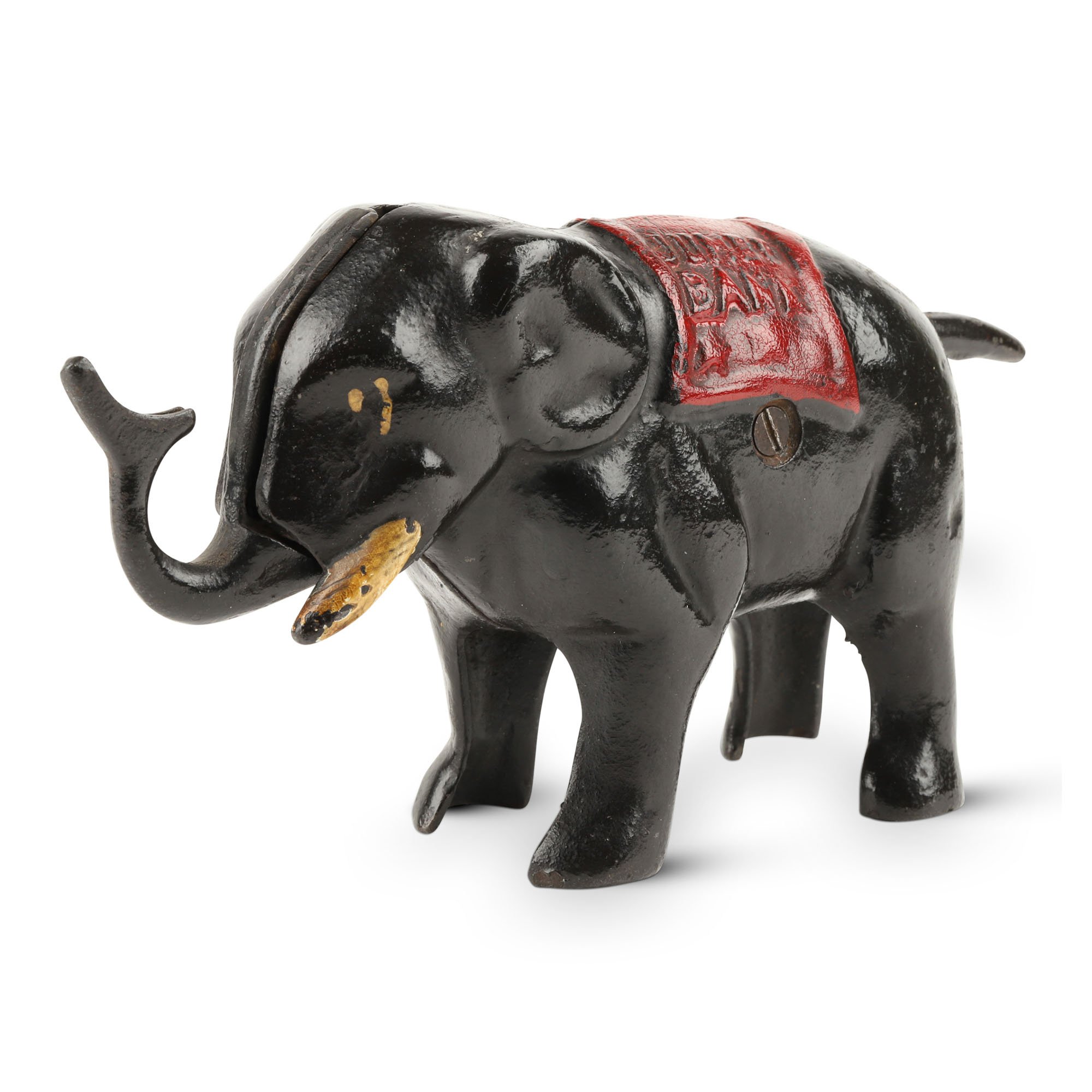

A painted Beaverton Toy Company Jumbo mechanical bank (lot 76) is also up for auction and “is a very important Canadian bank,” Jones says. Jumbo the circus elephant tragically died when hit by a train in St. Thomas, Ontario in 1885. When you put a penny on the end of his trunk and press his tail, the trunk lifts up and deposits the coin into his head.

This Beaverton Toy Co., Jumbo Mechanical Bank is offered as Lot 76 in the upcoming sale

Two important clocks in the sale include a Howard No. 5 Pennsylvania Railroad Clock with detailed provenance and sales history on original pieces of paper inside the lower door. These were the most precise timekeepers and were critical for railway schedules. The other is a Dixon Special trade stimulator clock. Trade stimulators like the Dixon Special were banned in many U.S. states in the 1940s and ‘50s, deemed a form of gambling. “This would normally have been an ordinary clock, however the mechanism was modified and that changed everything,” says Jones. The clock was found on the counter of a cigar store where customers would feed it a nickel and in return get a token which could be traded for a cigar. But every five ‘plays’ the clock would dispense two tokens for the price of one. “You’d always get one cigar so you didn’t lose money but the incentive was there to keep playing.”

This Howard No. 5 Pennsylvania Railroad Banjo Clock is offered as lot 157 in the sale.

This Dixon Special Striking Trade Stimulator Clock is offered as lot 166 in the sale.

The past 40-plus years have been rewarding for Jones and the passion for what he collected remains stronger than ever. “For me, it’s all been linked together – my career as an engineer, my interest in antiques and history, and of course this desire to understand how things work. I’ve had a very enjoyable ride.”

By Diane Sewell

Diane Sewell has been a writer for over 25 years, producing feature stories for some of the country’s top newspapers and consumer magazines, as well as client newsletters and commissioned books.

AUCTION DETAILS:

Advertising & Historic Objects

January 21, 2023. 9am EST.

Did you enjoy this story? Feel free to share it using the links below: