The ‘Fraktur’ Art of Anna Weber

‘Tree of 22 Birds’ comes to auction

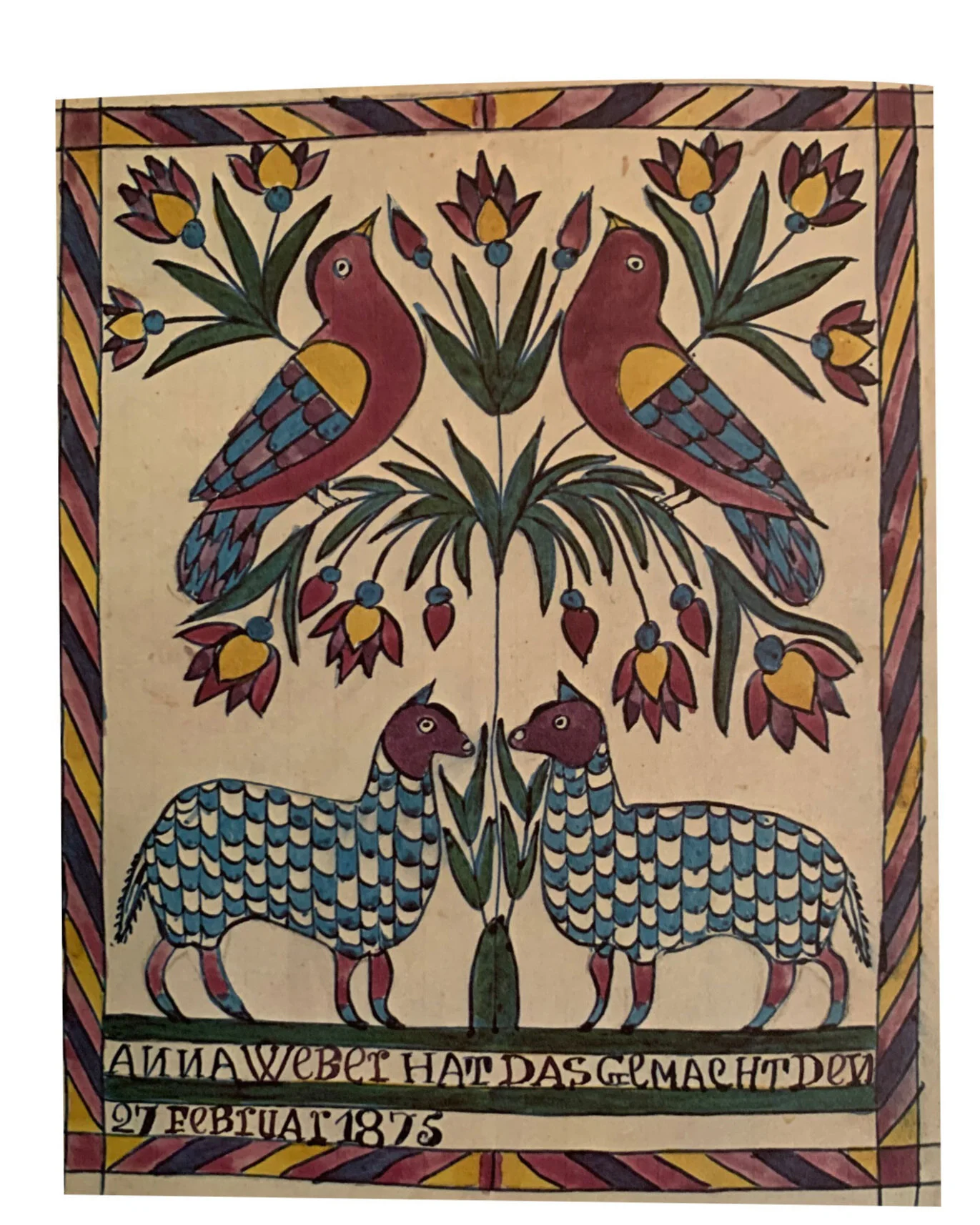

Candice Sauder holds the ‘Tree of 22 Birds’ Fraktur Painting by Anna Weber which will sell as lot 198 in Miller & Miller’s October 9th sale of Firearms, Sporting & Canadiana.

“History is everywhere - in the hand forged nail, in the smooth patina of a piece of wood, in the tiny strokes of Anna Weber’s pen” – Dorothy Duncan.

Offered in Miller & Miller’s October 9th sale of Firearms, Sporting & Canadiana is a selection of notable Canadian art. Currently lining the auction gallery walls are vibrant autumn hillsides by A.J. Casson, picturesque countryscapes by A.Y. Jackson and Homer Watson, and meticulous horse portraitures by Joseph J. Kenyon and Joseph Swift. Amongst these exquisite works resides a unique piece of fraktur art by an eccentric nineteenth century artist you should know more about: Anna Weber.

‘Fraktur art’ is an art form brought to North America by Pennsylvania-German Mennonite immigrants in the early 19th century. It originates from the term ‘Fraktur-schrift’ which literally means ‘broken writing’. While cursive script has its curves and tails, ‘Fraktur-schrift’ letters are broken up and condensed. Pennsylvania-Germans took this script and made it into an art form. How? They combined this letter style with colourful pen and wash drawings as a means of artistic expression. Often religious in nature, their artworks referenced folk cultures from the Rhenish Palatinate area of Germany – the homeland where they were forced to flee to escape religious persecution. Fraktur art became a way for this displaced group to feel connected to their roots, religion and community.

An example of the Fraktur writing style. This document was a tribute to Anna Weber’s grandfather Christian Weber, printed on the occasion of his death in 1820.

Anna Weber (1814-1888) had humble beginnings. By the 1820s, Pennsylvania had proven to be a difficult place for Pennsylvania-Germans to survive. Financial ruin prompted many families to migrate to Canada with the promise of cheap land and the faith in greater opportunities. Among these families were the Weber’s, a well-respected unit led by John Weber, a ministry deacon who spearheaded this wave of immigration and encouraged families to make the trek north. The Weber family arrived in Waterloo County, Ontario in April 1825 after a treacherous three-week journey through forests, fields, rivers and swamplands. It is believed that along for this journey came a bundle of Fraktur-style artworks that belonged to the Weber’s and would serve as inspiration for many of Anna’s future works.

Unlike many art forms, Fraktur art is not overly creative in imagination or concept, but rather served primarily as a way to ‘illuminate’ (decorate to emphasize) important scripture and documents. The Mennonite community considered artistic renders of the lands or the heavens to be sinful, as the Old Testament states: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image or any likeness of anything that is in the heavens above, or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth”. Fraktur art, however, was considered an acceptable method of creative expression as it centered around religion and family as its primary focus, unlike other ‘frivolous’ forms of art. Family documents such as birth certificates and genealogical records were carefully scripted in Fraktur-style lettering and adorned with intricate pen-and-wash symbols and borders. It was common for individuals to create Fraktur art in the pages of their bibles and songbooks, emphasizing verses and scripture that spoke to them.

An example of an ‘illuminated’ Fraktur birth and baptismal certificate (Geburts und Taufschein) of Johanes Bender by Johann Heinrich Otto

Some families would hire professional Fraktur-artists to illuminate their bibles and books, creating beautiful introductory pages to indicate the owner of the book in the case it was lost. Very few Fraktur artists would sign their artwork as it was seen as sinful to show pride in one’s work. Anna Weber, however, was the exception.

The ‘Memento Mori’ is a motif printed in many Mennonite religious books which depicts ‘Death as the leveller of all men’.

It is assumed that this piece by Anna Weber was inspired by the Memento Mori motif. The text speaks of her infirmity and old age, her desire to leave this life for the next, and acknowledges the levelling function of death. Note her signature in the lower left corner.

Anna Weber was known to have been of ‘unbrilliant’ mind, and a bit rebellious in nature, yet she would become one of the most respected Fraktur artists of all time. Her creative urges began at age nineteen when, much to the dismay of those around her, she began creating small stuffed animals and needlework samplers purely for her own enjoyment. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when her first Fraktur drawing was created, but the earliest known example is thought to have been created in 1854, shortly after the death of her father. Like most Fraktur works, her drawings were repetitive in nature, often featuring the same subjects of birds and flowers with patterned borders. These were the same motifs she’d seen adorning the books and walls of her community since childhood. Access to art supplies proved difficult in both cost and availability, so Anna created her own. She boiled rose petals for red hues, iris petals for purple, onions for brown, and saffron for yellow. She used ‘blueing’, a common bleaching agent at the time, for blue. These simple, bold hues became a defining feature in her work.

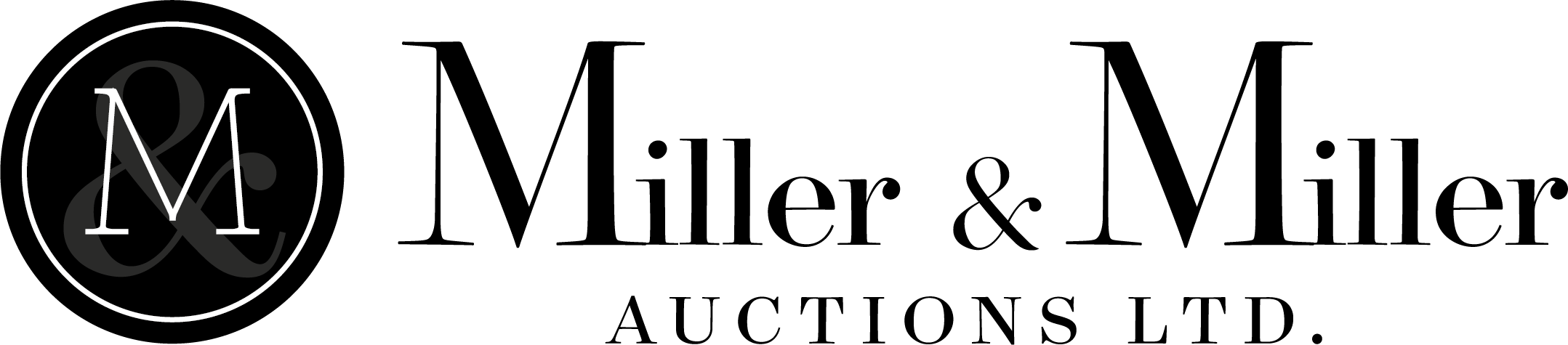

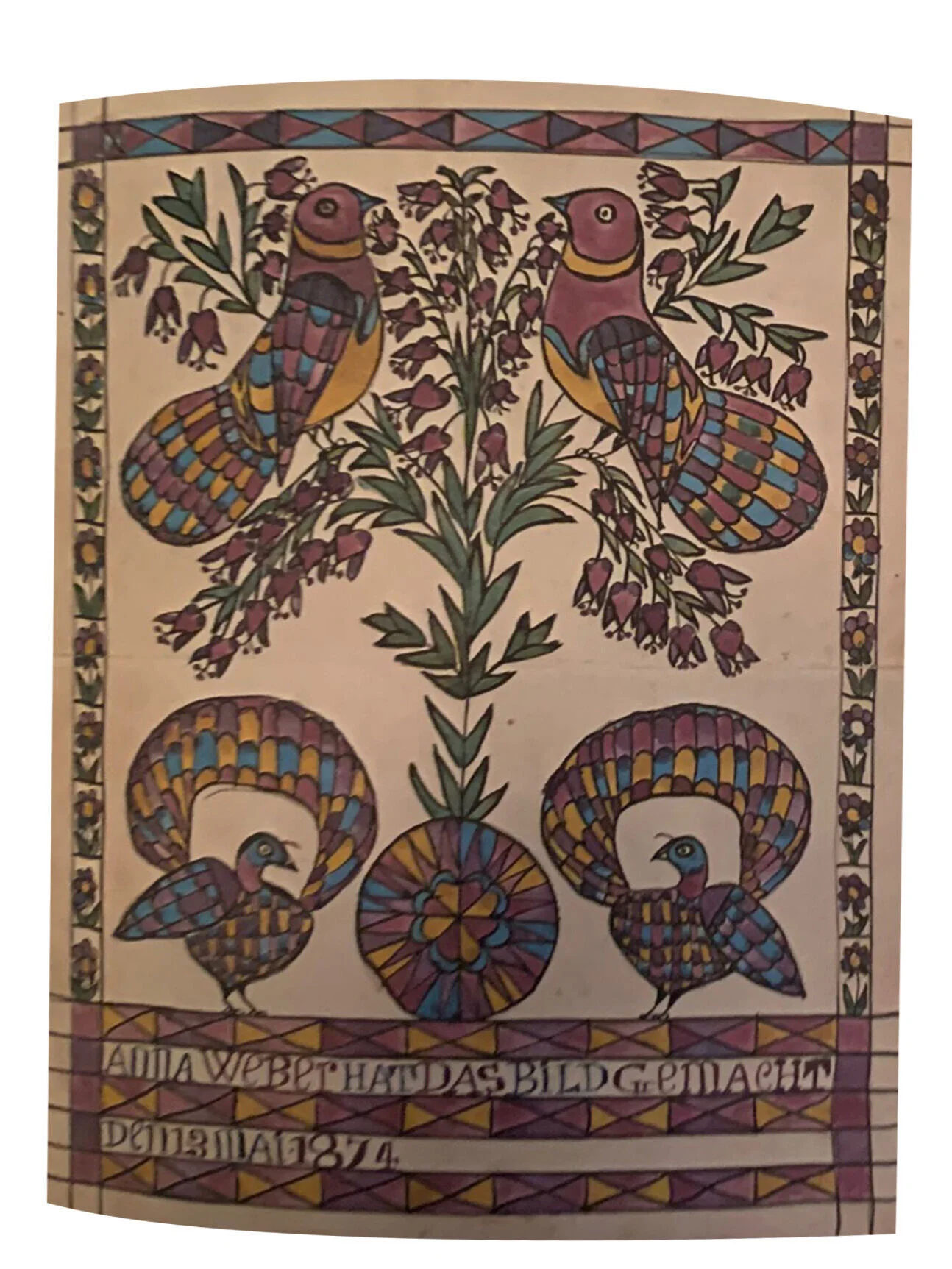

These two works by Anna Weber were created in 1874 and 1875. They are great representations of Anna’s style with bold hues, repetitive motifs and similar composition.

The largest and most elaborate of all Anna’s known drawings is the ‘Tree of 22 Birds’, 1970. It is pictured as Illustration 180 in ‘Ontario Fraktur: A Pennsylvania-German Folk Tradition in Early Canada’ by Michael S. Bird. True to her style in simple, bold hues and repetitive motifs, this earliest of her major works features eleven pairs of birds surrounding a central tree. This is offered as lot 198 in Miller & Miller’s October 9th auction.

Anna’s adult life was not an easy one as she struggled with medical issues such as dropsy (over-retention of water due to a kidney malfunction) which created swelling in her legs and feet and made walking only possible with assistance. Her mother died in 1864, leaving Anna without a stable caregiver. Between 1864 and 1888 no fewer than nine families are known to have given Anna a home for one or more short periods. She was seen as a burden by most families as she required care and contributed very little to household duties – and was often less-than-favourable in her demeanour. During this period in her life, Anna spent much of her time creating Fraktur art that she’d often gift to young children in the community, resulting in the inadvertent dispersal of her artwork across Waterloo county. After her death in 1888, these signature Anna Weber works would remain tucked away for generations.

In the 1970s, E. Reginald Good, author of ‘Anna’s Art’, spent ten months tracking down Anna’s artwork in the Waterloo Mennonite community. He was able to uncover an impressive number of undocumented Weber works, along with a multitude of tales about Anna and her family. His determination and research is to thank for providing Anna Weber with the recognition and appreciation she deserves.

Story by Tess M.

Take a closer look at the ‘Tree of 22 Birds’ Fraktur Painting by Anna Weber:

Sale Details:

Firearms, Sporting & Canadiana

October 9, 2021 | 9am

Did you enjoy this article? Feel free to share it using the links below: