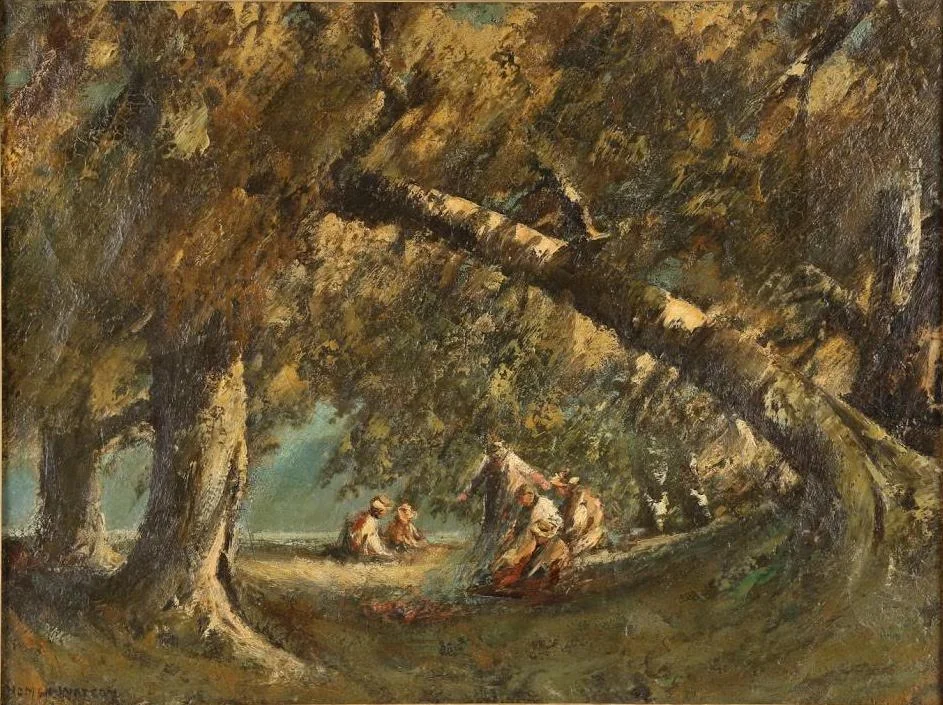

What the discovery of an undocumented Homer Watson masterpiece tells us about his secret life

Mystical in nature, this piece shares the characteristics of Watson’s later style

An undocumented Homer Watson masterpiece offered as Lot 364 in the upcoming sale at Miller & Miller Auctions.

Touted, at the height of his popularity, by no less than great British writer Oscar Wilde, as “the Canadian Constable,” Canadian landscape artist Homer Watson ended his days forgotten, neglected and in poverty. It’s the story in between that touches the imagination and the heart.

Born in 1855, in the sleepy village of Doon, south of the present day city of Kitchener in southwestern Ontario, young Homer Ransford Watson was known as a dreamy lad, more interested in watching the twilight fade into night than studying the sums on his slate. Tales were told of him arranging the food on his dinner plate into images, instead of eating it. Neighbours tittered at him being sent on an errand and never arriving at his destination—distracted by carving the image of a tree into a fence rail.

School was a trial for young Homer who doodled and sketched unendingly. He earned the title “addled” from his exasperated teacher. The death of his older brother Jude sent Homer further into his imagination and he roamed the landscape lost in his thoughts.

India ink, pen and pencil made up his first drawings. Then a gift from a kindly aunt of a set of brushes and a few tubes of paint set the lad’s imagination free to capture to wonders of nature. The rolling hills and secretive forests that made up the landscape around Doon and beyond would be his inspiration.

A Decision to be an Artist

At age 19, in 1874, Homer moved to Toronto to study art. “I did not know enough to have Paris in mind,” he explained to a friend. “Toronto had all I needed.” With no money for lessons, he set up his easel and stool at the Toronto Normal School (Teachers’ College). Homer spent endless days copying the Old Masters on display on the walls of the venerable institution.

Years later, in his Doon studio, he would pay homage to these influences by painting a frieze around the room’s upper walls. Each image displayed the great master’s name—Gainsborough, Constable, Rembrandt, Renoir. The artist added a small painting in their style.

Homer Watson’s Studio. The frieze bordering the upper walls pays homage to the great masters who influenced his early work. (Source)

Around 1877, Watson moved on to upper New York State where he fell under the spell of the Hudson River School. Following his muse, the young Canadian spent his days sketching along the Susquehanna and the Hudson Rivers. Watson’s paintings of this artistic period, such as “Susquehanna Valley,” (1877), and “On the Mohawk River,” (1878) with their vivid atmospheric moods show the influence of famed Hudson River landscape painter, American George Inness.

Becoming Famous

Returning home and taking up the subject matter with which he felt most at ease-- the gentle hills, the slowly-winding Grand River and the dark woods around Doon, Watson began to paint in earnest. He also joined the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA). This membership allowed him to display his works at various exhibitions around the province. Homer Watson struck gold with his first entry.

He’d entered “The Pioneer Mill,” a study of his grandfather’s tumbledown Doon sawmill, in the 1880 exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy. The public’s response to Watson’s work was overwhelming. A star on the Canadian artistic landscape was on the ascendant.

The work created an even greater sensation when the Marquis of Lorne, Canada’s Governor-General, purchased it as a gift for his esteemed mother-in-law, Queen Victoria. The price was $300. Homer Watson’s reputation as Canada’s premier landscape painter was solidified when his “Last of the Drouth” (1881) and “The Torrent” (1881) were added to the Queen’s Gallery at Windsor Castle. A century and a half before the internet, Homer Watson had gone viral indeed!

Such was Watson’s fame in England that British writer Oscar Wilde, on a tour of “the provinces” in 1882, asked to see Watson work. Dubbing him “Canada’s Constable,” (a reference to the great British landscape artist William Constable), Wilde also made a purchase. Orders for works by Homer Watson now began pouring in.

The income now allowed Homer to marry his longtime sweetheart, the former Roxanna Bechtel (Roxa). The couple purchased the Doon house that would be their home and Homer’s gallery.

Tragedy Marks a Change in Style

With the untimely death of Roxa in 1918, Homer began to look to the spirit world for answers to life’s complexities in. He hosted regular “table tapping” or séance sessions at his Doon home. They attracted an eclectic group of spirit-seekers, including artist Carl Ahrens and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.

Watson biographer Brian Foss points to Roxa’s death and Watson’s evolving connection to the spirit world as precipitating a shift to subjectivity in his painting style. “His work after 1918 exudes a gloom and darkness scarce present in his earlier work,” says Foss. “Watson substituted optical veracity and detail to unnatural colour and heavy brushwork.”

Foss points to paintings such as “Moonlight Stream” and “Evening Moonrise” as representative of this period of Watson’s artistic output.

Offered in Miller & Miller’s June 8th Sale, a newly discovered painting by Homer Watson, circa 1920. Mystical in nature, it shares the characteristics of his later style.

The Group of Seven and Homer Watson

Homer Watson’s reign as Canada’s most esteemed landscape painter would remain firm until the early 1920s when another phenomenon blew in from the north. Rejecting what they called the current European-influenced standard of Canadian art—Homer Watson being its most visible standard bearer--the Group of Seven painters: MacDonald, Jackson, Varley, Harris, Carmichael, Johnston and Lismer (Tom Thomson having downed in 1917) were determined to forge art that was truly Canadian.

At the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 in London’s Wembley Park where the Group of Seven was celebrated, the likes of Homer Watson were thrown to the curb. In a letter sent to National Gallery’s head Eric Brown, Watson lamented: “At any time now, we of the old guard can drop out and never be missed.”

In an attempt to modernize to the Group’s “rough and ready” standards, Watson again altered his painting style. Adding pink and purple to his palette, he also began to paint impasto. This new Homer Watson found few fans. Muriel Miller in her study, The Man of Doon quotes his reaction to artistic abandonment: “…my friends, my patrons I mean, think and say I am on the straight road to perdition if I continue this crime.”

Homer Watson, 1924, Moonlight Waning Winter. Watson later regretted modernizing his craft to compete with the Group of Seven’s “rough and ready” style. (Source)

Poverty and Loss

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 was devastating to Homer Watson. He had invested his entire savings into stocks and was rendered poverty-stricken by the disaster. In desperation, he turned to the National Gallery of Canada and its Director Brown for assistance. Brown had little sympathy. In his book, Refining the real Canada: Homer Watson’s spiritual landscape, Watson biographer Gerry Noonan says:

“Brown was quick to blame Watson for not making most careful provision for his old age… Every artist knows or should know that as he grows older fashions change and popularity wanes…therefore artists must make careful provision for the period if they are wise…”

Watson also appealed to his old friend William Lyon Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada. King’s response was sympathetic. “I’m even more disgusted, as well as disappointed with the action of the Gallery, than you yourself.” Disgusted King might be, but not to the extent of helping Watson out financially. He purchased one of Homer’s paintings but needed to be chased to pay up.

The end years of Homer Watson’s life were tragically dark. Deaf and embittered, “Canada’s Constable” was unable to afford heat for his home, or gas for his vehicle.

Homer Watson, near the end of this life, with artist friend Carl Ahrens. (Source)

Homer and his sister Phoebe, who had filled the role of Watson’s caregiver after Roxa’s death, threw themselves on the mercy of the Waterloo Trust & Savings Company. In exchange for a monthly stipend to provide the necessities of life, Homer Watson turned over all rights to his paintings. More than 450 of his works were now bank property.

On May 30, 1936, Homer Ransford Watson died. In her study of Watson, In Faith, Ignorance and Delight, biographer Jane Van Every quotes his stating, “’Well, I’m tired. I guess I’ll go and lie down.’ He did not rise again.”

In a tribute to his old friend, Prime Minister King called him “one of the noblest souls I have ever known.”

Watson’s Legacy

History has not treated Homer Watson with the dignity he deserves. More than a mere “landscape artist,” Watson captured the energy of an emerging nation. He remained too, over his lifetime, dedicated to conveying the power and the immediacy of nature. Finally, self-taught, Homer Watson surely must inspire other “dreamers” to follow their passions, to find heart’s contentment and mind’s fulfillment wherever it may lead them.

Story by Nancy Silcox

Item Estimate: $6000 - 9000

Lot Number: 364

Auction Details: Art, Antiques & Clocks - June 8th, 2019. 10 am.

Live Auction Location: 59 Webster St. New Hamburg, Ontario. N3A 1W8

Did you enjoy this article? Feel free to share it using the links below: