These clocks tell the tale of a remarkable Canadian triumph

Meet Arthur Pequegnat and his clocks.

Photographer Jon Dunford braces himself on the Pequegnat's "Montreal" model. Close to 200 Pequegnat Clocks hit the auction block on June 8, 2019 in Miller & Miller Auctions’ Art & Antiques Sale, featuring the Curt Davidson Pequegnat Collection.

The story of Arthur Pequegnat is one of triumph against the odds. Imagine a time before electricity and digital technology. A day and age when winding a clock was essential to keeping track of time. “Tick tock” was the sound of order. It meant catching a train. Silence was chaos. Arthur Pequegnat knew of the importance of timekeeping. He dared to envision a Canadian clock industry when it seemed impossible. Then he defied the naysayers and achieved it. What remains are his clocks: evidence of one man’s belief in his family and country.

30 years before Arthur Pequegnat entered the scene Americans had the clock industry “in the bag”. Between 1872 and 1886 three separate attempts by three Canadian clock companies failed miserably. Even a protectionist tariff extended by Canadian Minister of Finance Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley was not enough to save second company (The Canada Clock Company) from ruin. It did however name one of its models “Tilley” in honour of his 35% tax on the importation of foreign clocks! The Americans had the equipment, the scale, and the knowledge, and Canadians paid the price. When the Hamilton Clock Company launched in 1876, a prominent trade journal interviewed the floor manager: "I presume your hands are mostly Americans, as I do not suppose you could find Canadians skilled in this branch of industry". The manager replied, "On the contrary, out of fifty hands employed by us we only have two Americans". (Varkaris & Connell, 1986: 17). Canadian pride was not enough. Despite three separate attempts to compete with the Americans, all three companies were bankrupt by 1886.

1874. In the throws of a freak April snowstorm the Pequegnat family arrived from Switzerland to Berlin Ontario. According to The Pequegnat Story (Varkaris, 1982:9) never before, or since, had such a large family arrived in Canada at once. Fourteen in total. Two-by-two, Arthur and his father lead the pack “with a shotgun over each of their shoulders” should Indians be encountered (Varkaris, 1982:9). This scene foreshadows Arthur’s leadership in establishing his family, and eventually an entire industry, on Canadian soil.

1881. It wasn’t long before the eight Pequegnat brothers established themselves. They learned the language and disbanded with their Swiss skillsets to open jewellery stores across Southwestern Ontario. They used their collective buying power as a sort of family conglomerate. Within seven short years they opened 10 jewellery stores. Arthur, the eldest, was the ringleader. Arthur joined forces with his brother Paul to open stores in “Busy Berlin”.

Store interior of James Pequegnat's store in Stratford, circa 1910. As shown here, these family-owned stores became outlets for Pequegnat clocks.

Arthur Pequegnat was a revered figure. He had pensive eyes, saucer-like canted ears and a walrus moustache that that hid any glimmer of expression. He was a shrewd businessman with a tremendous nose for opportunity.

Arthur Pequegnat, in his heyday.

The Bicycle Boom – late 1880s to 1903ish

Long before bicycles became every Canadian child’s “rite of passage” into the world of the walking, they were an exclusive and elite mode of transportation. By the 1880s, innovations like the pneumatic tire and the diamond frame made riding a bike safe, efficient and fun – so much so that it sparked a “Bicycle Boom”, as historians call it. It wasn’t long before Arthur’s nose caught the scent of it.

Berlin, 1896. With bicycles on the brain, Arthur’s quaint little watch and jewellery shop seemed extra quiet. Bicycles whizzed past the shop like fleeting beacons of opportunity. Watches and bicycles were complimentary: both were mechanical devices geared to the privileged. Both were lucrative, but bicycles were the talk of the town. First he captured a piece of the action by opening a tiny bicycle repair shop in the back of his shop. Then he decided to focus exclusively on them. Savvy real estate acquisitions afforded he and Paul a spacious lot on Frederick street where they built a three-floor “Bicycle Emporium” to sell all of the leading makes. But soon that wasn’t enough either.

The Berlin & Racycle Manufacturing Company. 53-61 Frederick Street. Circa 1900.

“Our crank hanger does it”. That was the tenet of the “Racycle”, a bicycle innovation made by the Pequegnat brothers in conjunction with Miami Cycle & Manufacturing Company, Middletown Ohio. The Racycle was said to save the user “27%” of his energy as compared to the competition. Substantiated or not The Berlin Police Department bought it with a knife and fork. Racycles were issued to their entire staff to get a 27% edge on thieves!

A Berlin & Racycle Manufacturing Company envelope. Notice the claim, “Our crank hanger does it – Saves 27 per cent. pressure”.

Fads come and go. By 1903 “crank hangers” would mean little to a population mesmerized by a new kind of crank: the type hanging from the engine of a “horseless carriage”. By 1903 automobiles became so numerous that the Ontario Government developed a serial licensing system to keep track of all of them. This supplanted the bicycle industry in equal measure. The market was saturated, and demand was down. That’s when Arthur made his gutsiest move yet.

1900-1903. Proof of Concept.

1900-1903. Arthur was well aware of the ill-fated clockmaking attempts that preceded his. But he firmly believed in Canadians, and in his family. He saw the American imports. He knew he could do better for Canadians. He retooled the three-storey Racycle factory and added stamping and precision machining equipment downstairs. For shear aesthetics, the plates of every movement were coated in shiny nickel. Brother Philemon meticulously calibrated each movement with a precision wall regulator. Then, at incredible expense, Arthur worked in conjunction with Berlin Interior Hardwood to source the finest oak, mahogany and walnut for his solid wood cases. He demanded the wood be “quarter-sawn” to thwart cupping and reveal the radical grain. Brother George carefully fitted each of the cases with a movement. The result was a world class, Canadian-made clock. Now he had proof of concept. Selling them was the next battle.

1904. The Catalogue Release.

1904. A catalogue showing each model was mailed to every jeweller across the country trumpeting the news: “All true Canadians desire that our country should strive to reach a position in which every domestic article needed be manufactured at home…we have laid the foundation…”. The catalogue images were physical proof. The message was clear, “better value” than “foreign-made clocks”. The trade instantly recognized this value. Orders were arranged with school boards and Canadian railroad stations. Even Wrigley’s used the Pequegnat “Brandon” wall clock as a premium to incentivize storeowners to sell more gum. Soon the bicycle business would become a distant memory. “Pequegnat” was fast becoming a nationally recognized name synonymous high value, superior quality, and most importantly, the Canadian identity.

Pequegnat leveraged its position as a Canadian success story to sell clocks.

A marketing idea immortalizes the brand.

Here’s the part that immortalized Pequegnat clocks. For the cost of a piece of paper, each clock was assigned a meaningful “identity”. Some were patriotic names, others places in the world. They hit the jackpot, however, with Canadian cities. And not just any Canadian cities: the ones with the most potential buyers. It is no coincidence that of Canada’s nine largest cities in 1911, all nine appeared as clock model names in the 1913 catalogue.

A typical Pequegnat maker’s label, this one for “Montreal” mission clock. Models were named after large Canadian cities to attract more buyers.

The differences between some city models are almost indiscernible. For instance, the “London”, “Stratford” and “Colonial” shared the same case with only slight variations in trim or finish. It was a simple concept: models tributing different cities attracted more potential buyers. An inexpensive marketing strategy contributes to their collectability over a century later.

From right to left: the Stratford, London and Colonial models. Each model shares the same case with only slight variations. However, adding city models was a clever way to appeal to more potential buyers at minimal expense.

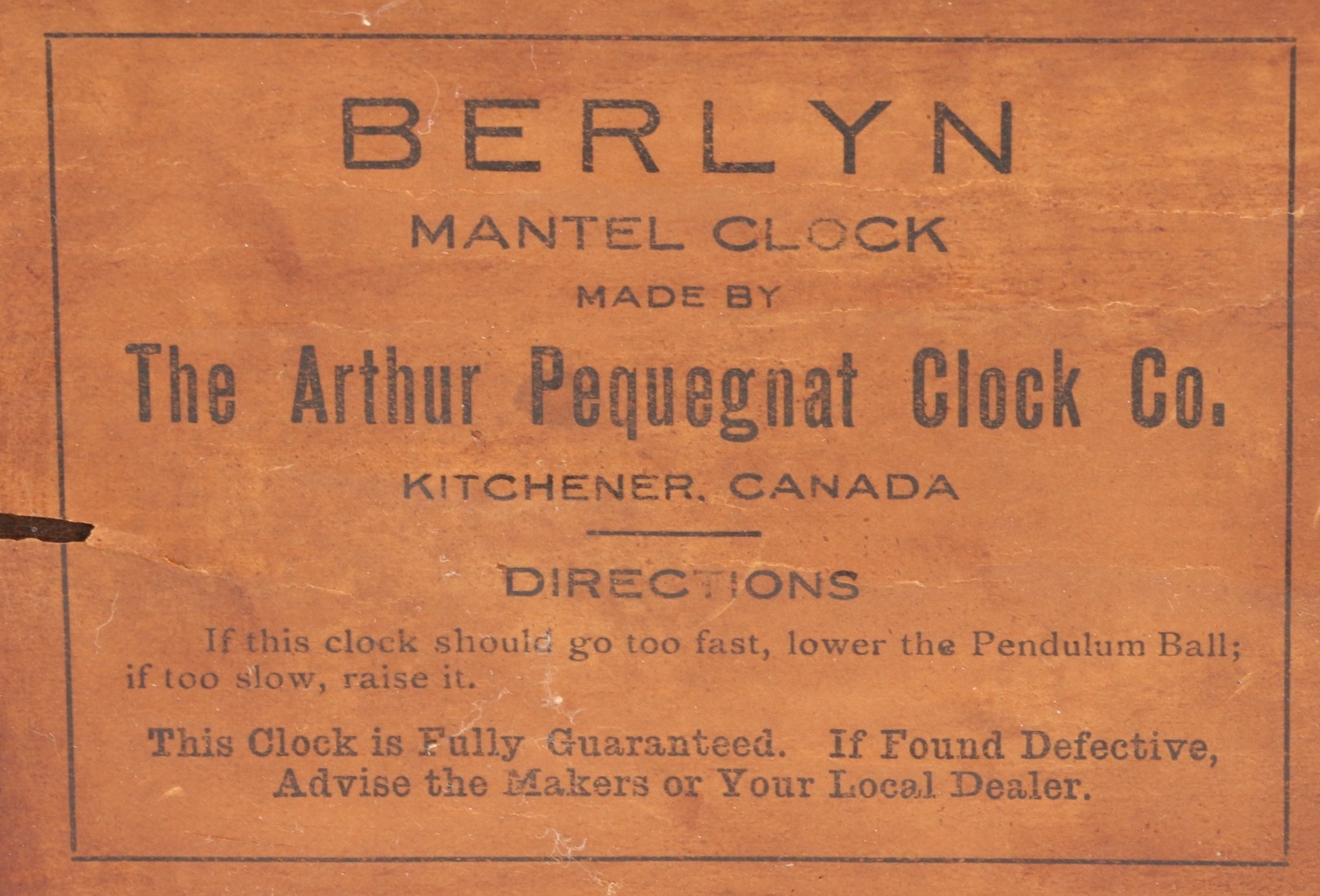

1916. World War I presented challenges. First, metal shortages affected clock production. White metal trim and feet were replaced with wood composite versions. Precious brass numbers became decals. Second, anti-German sentiment prompted a referendum to rename the City of Berlin “Kitchener”. It passed by a narrow margin and there was serious uproar. Berlin-News Record offices were ransacked, people were injured, and a bronze Kaiser-Wilhelm monument was dragged to the depths of a lake in Victoria Park. Pequegnat’s “Berlin” mantel clock now evoked bitterness. The strategy of city-named clocks had finally backfired. For whatever reason, the clock appeared as “Berlyn” (not “Kitchener”) for the 1918 catalogue. Then it was discontinued.

The Pequegnat “Berlin”, named after the city. Circa 1916. WW1 anti-German sentiment prompted a referendum to change the City of Berlin to Kitchener. The negative connotation forced Pequegnat to change the spelling of the model to "Berlyn" (not “Kitchener”).

Despite the adaptations made to survive World War 1, the Company would be limping by World War II. Arthur died in 1927. Surely he predicted its demise. He had a nose for that kind of thing. But this time there was no beacon of opportunity to chase, nor the energy to chase it. The streets were lined with trophies of the Industrial Revolution: vertical wooden poles that carried strings of hydro-electricity into every household. They would soon make the winding of a clock a needless, archaic practice. All production ceased by 1943.

Close to a century later, Pequegnat clocks continue to circulate among collectors, decorators, and Canadian history buffs. Curt Davidson was among the collectors. On June 8th, 2019, his entire collection hit the auction block at Miller & Miller Auctions in New Hamburg Canada. It contained a full run of Pequegnat models (with variants) totalling close to 200. Never in history had such a collection been offered to the market, entirely without reserve. Using Davidson’s clocks, Miller & Miller re-created a 1911 Toronto Exhibition Pequegnat clock exhibit in its gallery. This same exhibit won The Pequegnat Clock Company a silver medal nearly a century ago.

Using clocks from the Curt Davidson’s Collection, Miller & Miller Auctions re-created a 1911 Toronto Exhibition Pequegnat clock exhibit in its gallery. This same exhibit won The Pequegnat Clock Company a silver medal nearly a century ago.

Story by Ethan Miller and Jeff Crouch

Special Contributions from Paul Johnson, Bruce Dyer, Lorne Shields, Joe Schneider, Ron Pequegnat, Tom Pequegnat & James Pequegnat.

Resources:

Varkaris, Jane & Costas (1982). The Pequegnat Story: the family and the clocks.

Varkaris, Jane. Connell, James E. (1986). The Canada Hamilton Clock Companies.

Four of Curt Davidson’s Clocks, and their stories:

Did you enjoy this article? Feel free to share it using the buttons below: