How the letters ‘CCM’ became part of what it meant to be Canadian.

John McKenty is a Canadian author and historian whose research culminated in the publication of his 2011 book, Canada Cycle & Motor: The CCM Story. His pursuit signaled the birth of his own vast and important CCM Collection, preserving a story that was in danger of being lost forever. It is slated to be sold by Miller & Miller Auctions on Saturday December 7, 2019.

Bikes in summer, skates in winter. For most Canadian youngsters, the initials CCM were synonymous with growing up in Canada.

But what did the letters stand for?

For the answer, one must turn to the dawn of the 20th century when the bicycle was everywhere. The advent of the ‘safety bicycle”, with its two wheels driven by a sprocket & chain and stopped by a coaster brake, meant just about anyone could ride a bike, a fact that had sent sales skyrocketing.

The bicycle was big business and Walter Massey (1864 – 1901), president of Toronto’s Massey-Harris Manufacturing Co. knew it. He wanted in on the action. It only made sense. As the British Empire’s largest manufacturer of farm equipment, Massey had the factory, equipment and distribution network needed to successfully enter the bicycle business.

What Massey didn’t have was a bicycle patent. It was an issue he addressed by sending two of his men to Hartford, Connecticut, to visit Colonel Albert Augustus Pope, the world’s largest maker of bicycles.

Upon their return, the men informed Massey that their company could begin to make bicycles under license with the Pope Manufacturing Co. In return, they were expected to pay the Colonel $1.00 a bicycle which wasn’t a problem since Massey intended to sell his bikes for approximately $100.

Thus in 1896 the Massey-Harris Manufacturing Co. began to produce its Silver Ribbon bicycle and shipping them throughout the British Empire, including England, Australia and New Zealand.

Then in 1898 Massey learned that the American Bicycle Co., an amalgamation of 42 bicycle makers, including Colonel Pope’s, was headed to Canada. Fearing his bicycle business would suffer, Massey enlisted the aid of Joseph Flavelle, head of the Robert Simpson Co., George Cox, head of Canada Life, Warren Soper of the Dunlop Tire Co. and E. R. Thomas of the H.A Lozier Co.

Their plan was simple.

They would buy up Canada’s four leading bicycle makers and combine them with Massey’s own bicycle works to form one company.

And that’s what they did.

They bought the Welland Vale bicycle works in St. Catharine’s (Perfect), the Goold bicycle works in Brantford (Redbird), the H.A Lozier Co. (Cleveland) and Gendron bicycle works (Reliance) both of Toronto and formed one company - Canada Cycle & Motor Co.

Launched in September 1899, amid considerable fanfare, the company immediately faltered.

The growing popularity of the automobile meant bicycle sales were on the downslide. On top of that, the company struggled to manage its five factories, each with a myriad of models and an array of inventory. Marketing was also a nightmare.

To make matters worse, investors had bought $2 million in company shares under the assumption that with successful businessmen such as Massey, Flavelle and Cox at the helm, it was a sure thing. Disappointed, they began to refer to the company directors as “The Big Syndicate” and to accuse them of skimming off company profits. Faced with numerous lawsuits, the directors spent most of the next three years in court.

With things getting desperate, in 1902 Joseph Flavelle did what would turn the company around. He hired Thomas Alexander Russell to manage it.

While the company directors were, for the most part, a mysterious lot of millionaires, who knew far more about making money than they did bicycles, Russell was different. Born in 1877 he grew up on a farm in southwestern Ontario. He knew what farm boys know. He knew machinery. He knew how to use it, how to fix it and he rode a bicycle. Held in regard by employers and dealers alike, Tommy Russell was often seen walking the factory floor.

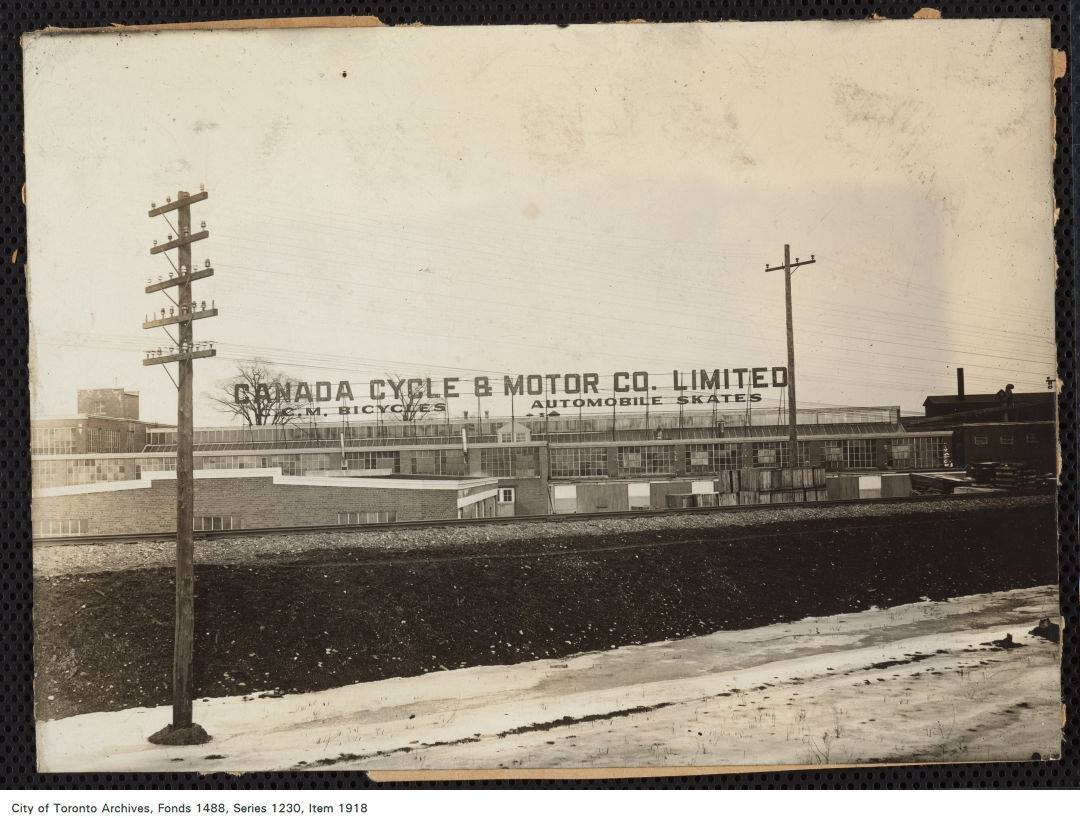

By the end of 1903 Russell had shut down the company’s factories in St. Catharines, Brantford and Toronto and centralized the company’s production in one location – the old H.A. Lozier factory at 408 Weston Road in the area known as Toronto Junction.

Russell knew full well that the company had to get into the production of automobiles sooner rather later. As a result, in 1905 Canada Cycle & Motor launched its Russell Motor Car, Canada’s first Canadian-made car. It was an immediate hit.

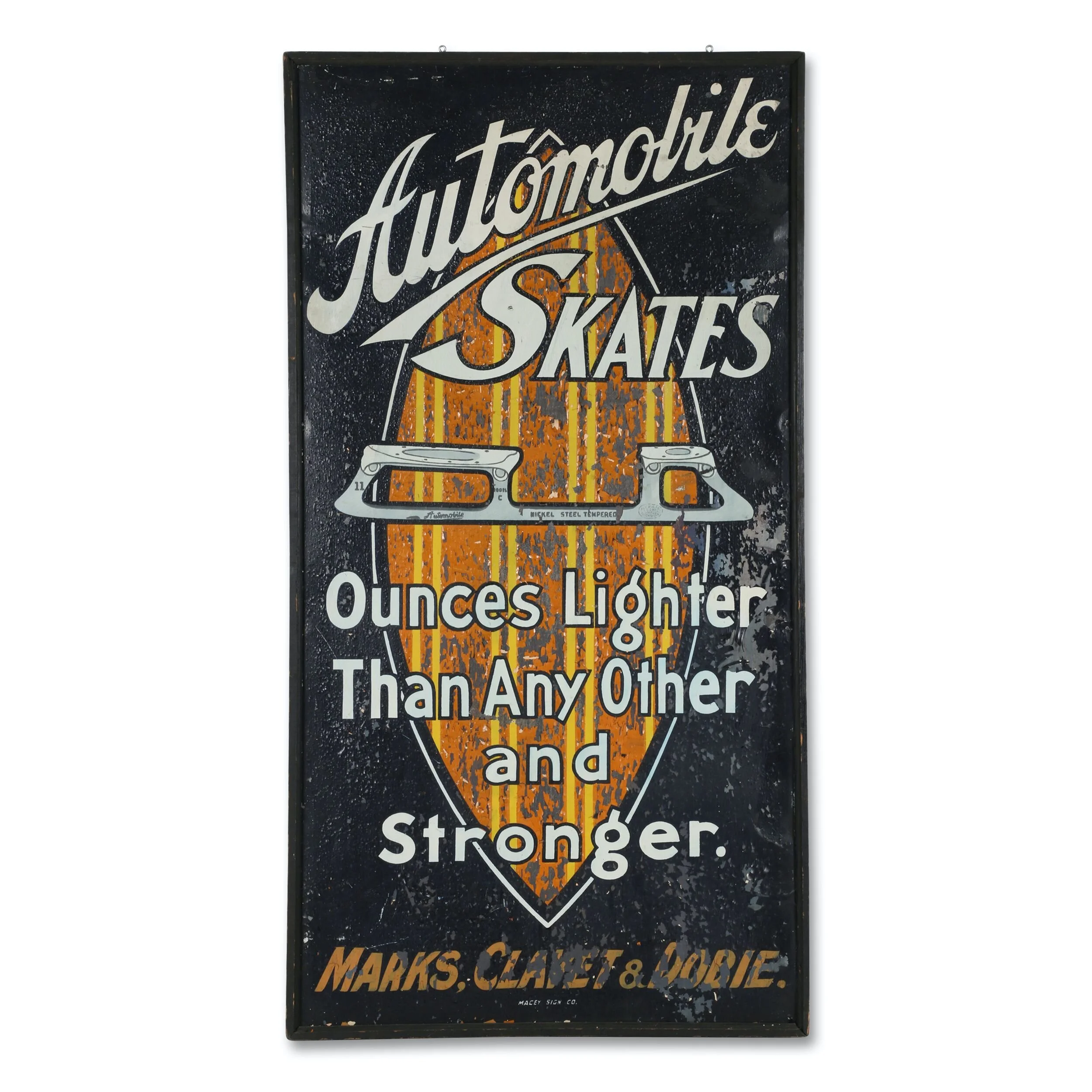

At the same time to keep his workers busy in the winter when bicycle sales were slow, he had them begin to use the stainless steel from the Russell Motor Car to make skate blades, aptly called Automobile Skates. In those days, skate makers made the blades while the shoemakers made the boots.

By 1915 the Model T had taken over Canada’s roadways and Tommy Russell knew he couldn’t produce a car in Toronto for what Henry Ford could in Detroit or Gordon McGregor could in Walkerville (Windsor). So in 1915 he sold the automotive division of Canada Cycle & Motor to John North Willys of the Willys-Overland Motor Co.

With a renewed focus on its bikes and sporting goods, in 1917 Canada Cycle & Motor opened a new state-of-the-art factory on Lawrence Ave in the area known as Weston. By now the company accounted for 85 per cent of all bicycles made in Canada.

The CCM bicycle was given a substantial boost in the mid-twenties when Willie Spencer broke five world records and won the American speed championship three times aboard his CCM Flyer.

When he retired from competitive racing, Spencer managed the popular 6-day bicycle races at Maple Leaf Gardens where his star attraction was a young rider from Victoria, British Columbia, by the name of William “Torchy” Peden (1906 – 1980).

With his flaming red hair and considerable size – 6’3” 220 lbs. – Torchy and his CCM Flyer were a sight to behold as they circled the 6-day saucer. Peden represented Canada in the 1928 Olympic Games and coached Canadian Olympic Teams in 1932 and 1936

From 1929 – 33 Peden won 24 of the 48 races he entered and was a perennial world champion. In recognition of his accomplishments, in 1938 CCM presented him with a gold-plated version of his CCM Flyer that sits today in the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame. Upon his retirement from racing, Torchy became a CCM rep for the Chicago area.

In 1936 CCM introduced the only bicycle for which it actually sought a patent. Known as the CCM Flyte, and designed by company employee Harvey Peace, its patent application filed October 23, 1935, described the bicycle depicted as being both novel in design and practical in its ability to absorb the shocks and vibrations of the road.

Despite being hailed as stylish and functional, the Flyte never became a big seller and its production ceased in 1940. Whether it was too expensive ($45) or the forks were too weak, in the end the Flyte’s limited production ensured its rarity and eventual desirability among CCM bicycle collectors.

By the 1930s CCM had made the transition from promoting bicycles to adults to promoting them to young people. Each year the company produced thousands of scribblers for use in schools across Canada. When youngsters received their CCM scribbler, they were delighted to find the company’s newest bicycles and skates on the inside, while the back of the book suggested they ask their parents to buy them a new CCM bicycle for passing.

By the 1930s the company was offering a full line of skates and hockey equipment. Having introduced its Automobile Skate in 1905, CCM dominated the Canadian skate market until 1927 when the Western Shoe Co. of Kitchener, Ontario, owned by the Bauer family, introduced the first skate in Canada to leave the factory with the blade attached.

It was a challenge to which CCM wasted little time in responding. Looking for a boot to match the Bauer boot, CCM turned to Manitoba shoemaker George E. Tackaberry (1834 – 1937). Tackaberry, who specialized in the construction of orthopedic shoes, had developed a skating boot for his next-door neighbour NHL defenceman Joe Hall.

With its combination of innovative design and meticulous craftsmanship, the Tackaberry boot used a moisture-resistant kangaroo hide with a snugly-fitting reinforced heel and toe, an improved arch support and a thicker tongue. Said to “fit like a glove,” when combined with the CCM Prolite blade, the “Tack” skate became the instant favourite of amateur and professional hockey players throughout Canada.

Describing their new skates as “Matched Sets” and claiming the boot and blade were scientifically matched before leaving the factory, the company hired NHL stars, such as Charlie Conacher and King Clancy, to endorse their skates.

Eventually the best-known player to do so was Bobby Hull. Throughout the sixties no player was more recognizable than Hull. Known as the “Golden Jet,” nothing brought more excitement to the TV screen on a Saturday night than Hull with his blinding speed and blistering shot.

In 1968 Hull signed a contract with CCM that paid him $25,000 a year for five years, an amount unheard of at a time when endorsement deals were scarce. It was so lucrative it landed Hull on the cover of Time magazine and even benefited Hull’s team mates who received a cut every time a photo of Hull was used showing the Chicago Blackhawk insignia.

By the 1970s growing financial difficulties and strained labour relations had led to yearly operating losses at CCM. When the 10-speed craze hit in the early 70s the company wasn’t ready for it. Disgruntled workers were asked to produce more and more bicycles, faster and faster, on outdated equipment. Quality control became a thing of the past. The company’s reputation suffered and sales declined.

Imports from England, Italy and Japan decimated CCM’s once considerable market share. The company became dependent on government loans to keep it afloat. By 1983, however, the well had run dry and the company was forced to declare bankruptcy.

Along the way the company had lost the guiding principle upon which Tommy had turned the company around. Russell called it “Shared Responsibility” – the commitment “to give the public a good article at a fair price and to give to the working man the fullest share possible of the returns he helped produce.”

It was a sad end for a company that once was as much a part of the Canadian psyche as the seasons themselves.

Story By John McKenty

Auction Details: Advertising & Historic Objects - December 7th, 2019. 9 am.

Live Auction Location: 59 Webster St. New Hamburg, Ontario. N3A 1W8

Did you enjoy this article? Feel free to share it using the buttons below: